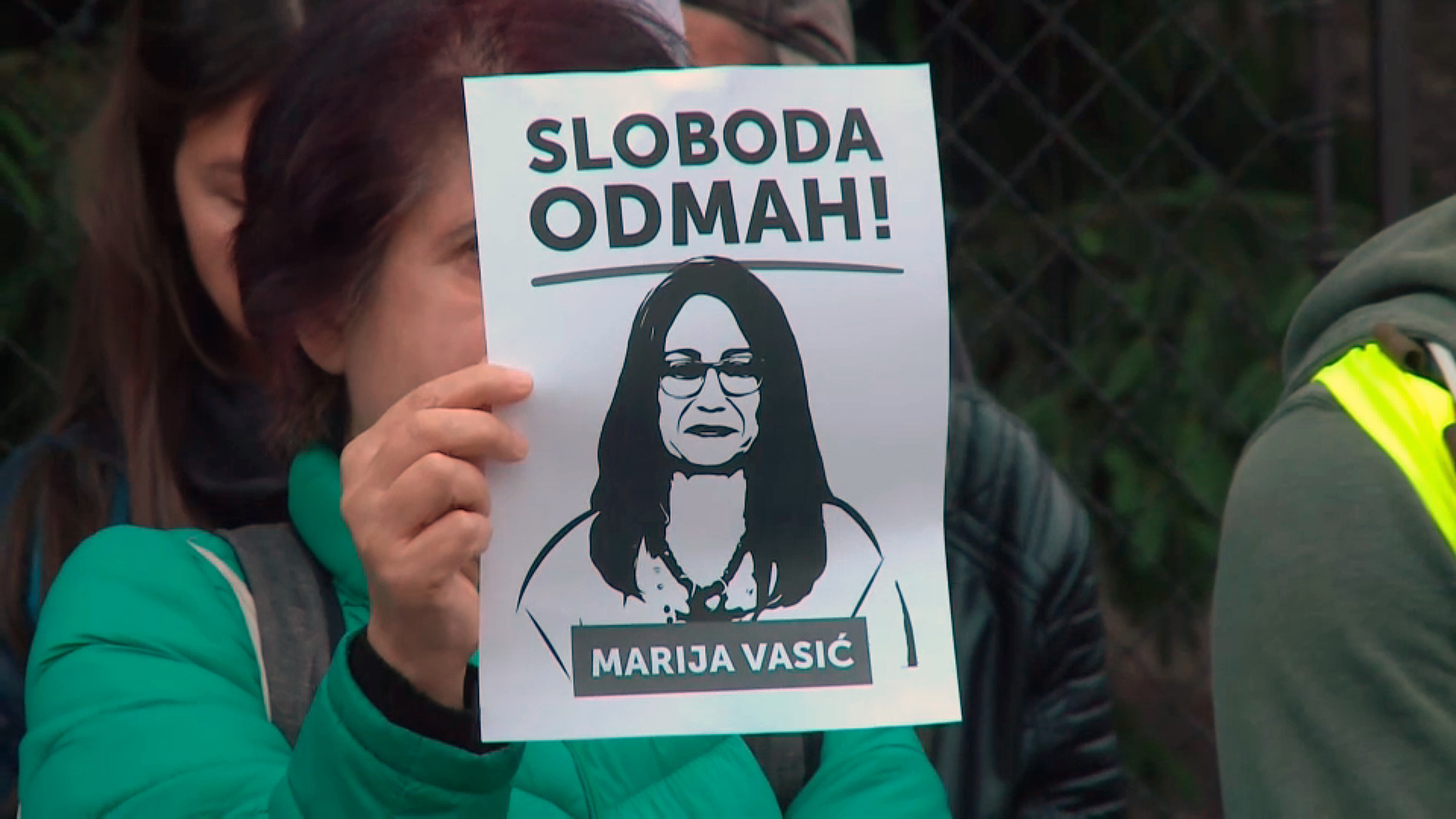

Professor of sociology Marija Vasić from Novi Sad is the first political prisoner in Serbia since the democratic changes of 2000. She was arrested together with activists and members of the Movement of Free Citizens after unlawful wiretapping, and a fabricated trial for planning a coup d’état is underway against her and her associates.

At the beginning of the year in Novi Sad, four activists of the Serbian Progressive Party attacked a group of students with baseball bats and broke the jaw of a female student of the Academy of Arts. President Aleksandar Vučić pardoned the attackers and called them “heroes”.

During a commemorative silence in Belgrade, a female student of the Faculty of Law, Sonja Ponjavić, who was standing on the sidewalk, was attacked by a maddened driver. He accelerated, hit the girl and carried her on the hood for several meters, after which she fell and sustained serious head injuries.

In Novi Sad, another enraged driver, after the commemorative silence, drove out of his lane and deliberately struck journalist and civic activist Marija Srdić at a pedestrian crossing.

According to N1 journalist Lea Apro and professor of the Department of Media Studies Smiljana Milinkov, police officers used excessive force. There are countless examples of violence against girls and women who are publicly opposing terror and dictatorship at student and civic protests for more than a year.

What distinguishes violence against dissenters at these protests from those in the 1990s and early 2000s in Serbia is that the authorities, the repressive apparatus, and regime loyalists are targeting young girls and women.

Not only to break rebellious women, but to do so publicly and as an example to everyone. To make the situation even more panic-inducing for the regime, girls and women are more present at the student and civic protests of 2024/25 than at any previous protests in Serbia. At times, there is an impression that they are more active in the front rows than young men and men.

The aforementioned victim of the attack, today a councilor of the Bravo Civic Movement in the Novi Sad City Assembly, Marija Srdić, believes that for the first time in the dramatic period we are living through, women are fully equal in the struggle or are even leading the protests. She notes that in the 1990s, a re-patriarchalization of society began in Serbia, retrograde processes, the withdrawal of women from the public sphere, and their complete absence from political life, where at that time they made up only a few percent of parliament.

The patriarchal regime has no plan, but acts instinctively and organically, because nothing symbolizes freedom as much as a rebellious woman. All women known to have suffered violence by the regime are once again in the fight, Srdić adds.

The goal is not only to intimidate part of the demonstrators, but to preserve the patriarchal order in society. The main line of social hierarchy in which “he defends, and she gives birth”. Allowing “female blockers” to stand in front of police cordons or to criticize the regime means showing weakness before those considered inferior.

Every emancipation of women is a step toward a freer society. Or, speaking in the terms of Umberto Eco about eternal ur-fascism, permanent war and heroism are tough games and not for women. Machismo is part of every authoritarian cult, and projecting the will to power onto sexual issues is spontaneously articulated by the commander of the Unit for the Protection of Persons and Facilities of the Serbian Ministry of Interior, who publicly threatened female student Nikolina Sinđelić with rape.

Threats and violence most clearly expose the regime of the 1990s and the apprentices of the Chetnik Serbian Radical Party and the Socialist Party of Serbia. After three decades of spreading across the region of the former Yugoslavia, war is returning to Serbia. Women in the camps of the region were treated as objects of sexual prey, and for the first time in global judicial practice, the International Tribunal in Hague systematized rape as a war crime and a crime against humanity.

Systemic belittling of women is the foundation of a patriarchal society, and Serbia is among the Western Balkan countries with higher rates of femicide.

Although the youth uprising may not fulfill political expectations, several legacies of social change in Serbia will remain. First of all, a new patriotism, over which radicals and “ćaci-nationalists” will no longer have a monopoly. Then a new multiculturalism, or more precisely multi-traditionalism, in which the coexistence of different peoples and religions is more than possible, as demonstrated by young people from Novi Pazar who walked across Serbia and whose Muslim headscarves were kissed by people along the way.

The legacy of equality is a new emancipation of girls and women in politics, through the struggle against dictatorship. And this, after the re-traditionalization of the entire region, is probably the greatest civic achievement at the level of a national liberation struggle.

No one disputes that there is equal representation in parliament and certain institutions thanks to quotas for the underrepresented gender, primarily in electoral legislation. This has been formally achieved, but it is still quite far from essential equality woven into the everyday lives of women and men. In practice, these are often token figure – women placed in positions as MPs, ministers, and presidents of parliament or government. In macho nationalism and authoritarianism, there is no equality.

One should not go to the other extreme and idealize a time in which certain future female leaders in Serbia will have conservative and nationalist ideologies, in the spirit of Marine Le Pen and Alice Weidel.

In a village in Vojvodina, two sisters—one a high school student, the other a university student—after breakfast took the tractor keys and told their father they were going to block the main village intersection, regardless of what he thought about it.

The rebellion of female citizens is a complex phenomenon that has entered every pore of society in Serbia. They are educated, diligent, and freed from fear.

Boris Varga. Serbian political scientist and journalist.

The articles published in the “Opinions” column reflect the personal opinion of the author and may not coincide with the position of the Center