The oil industry of Serbia has found itself on the verge of catastrophe due to its dependence on Russia. The sanctions strike, aimed at weakening the Russian energy sector and undermining the financing of the war, simultaneously jeopardized the entire Serbian energy system, which turned out to be part of the Russian network. Belgrade had long sustained the viability of Russian shadow schemes while attempting to demonstrate its commitment to friendly relations with Washington and progress in European integration. But the era of ostentatious “Serbian neutrality” has come to an end.

Energetic Sanctions in the Energy Sector

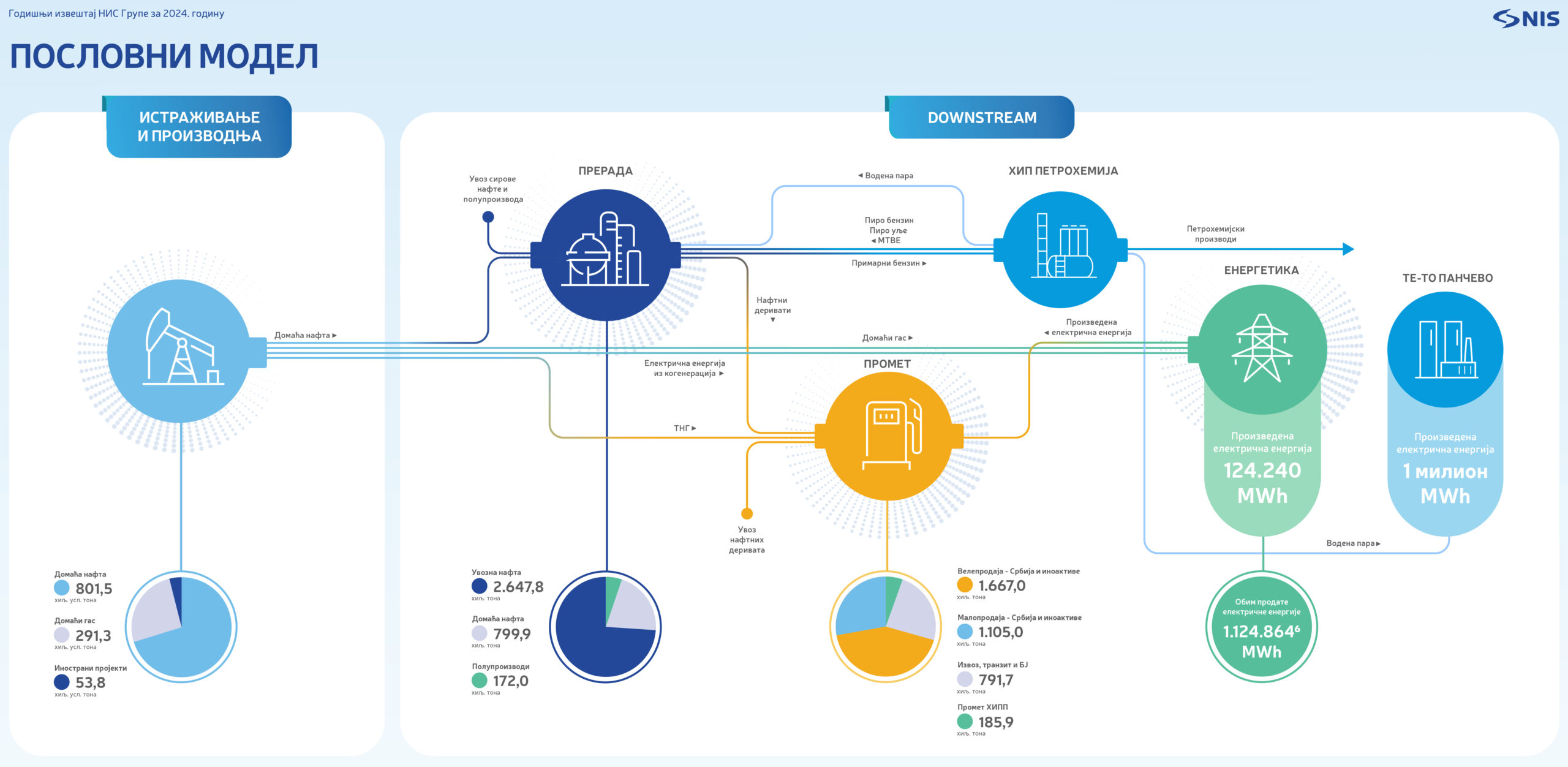

On October 8, U.S. sanctions against the company Naftna Industrija Srbije (NIS), imposed back on January 10, 2025, came into force. This company is controlled by Russian entities, particularly the state-owned Gazprom Neft, so the strike was not aimed at Serbia but at the Russian energy sector. Yet the problems emerged precisely for the Serbs, due to their energy dependence on Russian supplies.

NIS controlled between 80% and 90% of the domestic fuel market in the Balkan country. The remaining share was almost entirely controlled by another Russian company, Lukoil, which came under a new wave of U.S. sanctions on October 22, 2025, when the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) added the company to the SDN list under Executive Order 14024.

Fearing secondary sanctions, foreign companies ceased their dealings with NIS. Problems arose with crude oil supplies, since the pipeline from the Adriatic terminal and the terminal itself belong to the Croatian company JANAF, oil was delivered by international firms, and payments went through foreign banks. Even salaries for NIS employees were processed through international payment systems, while the national payment system DinaCard is tied to American partners. Paying for gasoline at Russian gas stations would constitute a violation of sanctions; therefore, Serbs could not pay for fuel with banking cards.

Moreover, the Americans warned that sanctions-related problems could also affect the National Bank of Serbia, since the Pancevo Refinery operates through the IPS Serbia payment system, managed by the National Bank of Serbia. A catastrophic economic scenario caused by dependence on Russian energy companies became increasingly realistic.

How Did Serbia End Up in This Position?

After the Yugoslav wars, which Serbia lost, the country found itself in a dire economic and political situation. Following the economic blockade of the Milošević regime and the loss of control over the province of Kosovo, the Serbian state needed allies. The situation was further complicated by the 2007–2008 economic crisis. Western investors withdrew their money from the Balkans, and no other sources of budget replenishment were in sight. The “brothers” from Moscow came to the rescue. Russia offered an epic “Gas Contract” and support on the Kosovo issue. But not without self-interest. Taking advantage of the “brother’s” difficult position, Moscow monopolized Serbia’s energy market and also took over the only large oil refinery in Pancevo. The Serbian government sold a stake in the company to the Russian state-owned Gazprom Neft for $500 million, while the Serbian State Audit Institution estimated its real value at $2 billion. The agreement provided that Gazprom Neft would acquire 51% of NIS shares, while the Serbian state would retain 49%. The official explanation from Belgrade was “a political partnership with Moscow,” which was supposed to ensure energy security and Russia’s support on the Kosovo issue. “Signing an energy agreement with the Russian Federation is a forced and realistic step for Serbia. Russia is our friend and partner, and in times when others turn away, it is natural to rely on those who extend a helping hand,” said former Prime Minister of Serbia Vojislav Koštunica, who was the “father” of the great deal.

Of course, ordinary Serbs did not like the sale of the only oil refinery below its real price, and the government decided to distribute shares from the state’s portion. Each Serbian citizen received five shares worth about 30 euros in total.

The Oil Yoke

However, as it turned out, for Russia this contract became not so much an economic as a geopolitical instrument. Through NIS, Moscow obtained in Serbia not merely a source of income but also a lever of political influence. Control over the Pancevo Refinery, the network of gas stations, and strategic fuel reserves allowed Russia to dictate the terms of Belgrade’s energy policy. In effect, NIS became Moscow’s “energy embassy” in the Balkans — a channel of influence operating parallel to diplomacy.

Over the years, the role of NIS only increased: the company invested in social responsibility projects, funded local initiatives, scientific programs, and cultural events — forming the image of a “benevolent investor.” At the same time, such programs created soft dependency in the regions where NIS was the largest employer or benefactor. Serbian experts repeatedly warned that this was a form of economic paternalism disguising political loyalty.

Therefore, the current Serbian energy crisis is not an accident but a direct consequence of the strategic mistake made fifteen years ago — the sale of energy sovereignty in exchange for Moscow’s political support.

It is also worth recalling the Serbian economy’s dependence on “special conditions” for Russian gas supply, where the price of energy is determined not by the market but by the Kremlin, depending on Belgrade’s “behavior.” The picture thus becomes even more dismal.

After Russia’s war against Ukraine began — that is, as early as 2014! — and especially after the full-scale invasion in 2022, Serbia, like all other European countries, had the opportunity to rebuild its energy sector and rid itself of total dependence on Russia. But that did not happen.

Brothers in Oil

When in 2025 the U.S. added NIS to the OFAC sanctions list, the blow to Serbia became inevitable. U.S. representatives repeatedly emphasized that the goal of the sanctions pressure was to undermine the financing of Russia’s war through its oil industry. It was intended to weaken Russian control, but in practice it struck the entire Serbian energy system. The company that provided up to 90% of the fuel market was cut off from international finance and supplies. This exposed the real cost of “brotherly assistance”: Serbia received cheap oil — and lost the freedom to make energy decisions. It turned out that the country’s energy sector is entirely dependent on Russia, and the Serbs would have to pay according to Russian terms.

Belgrade found itself between two fires. On one side — Washington and Brussels, demanding a reduction of Russian presence; on the other — Moscow, threatening to halt energy supplies, including gas. A way out of this trap has not yet been found.

After the sanctions were announced, NIS tried to save the Russia-controlled supply system while avoiding full U.S. blockade. The Serbian government and Russian owners resorted to a series of maneuvers meant to create an appearance of “restructuring” without any real change of control. The first step was the dilution of Gazprom Neft’s share: in September 2025, about 11.3% of shares were transferred to a little-known Intelligence company from St. Petersburg, formally unrelated to the energy sector. In reality, the owner of Intelligence remained Gazprom, through Gazprom Capital. On paper, this appeared as a reduction of Russian presence, but in fact, control remained unchanged — a legal façade concealing economic dependence. The attempt to cover Russian traces was naive. The control persisted, only acquiring a more complex form. And the Americans at OFAC understood this perfectly.

Searching for a “Fifth Corner”

At the same time, NIS began seeking alternative sources of crude oil to diversify imports. However, these attempts quickly ran into geographic and logistical realities. After the blocking of the Croatian JANAF terminal, through which the main oil flow passed, Belgrade bet on river transport — barges along the Danube.

Barge deliveries along the Danube were a short-term technical solution, theoretically allowing partial circumvention of controls. But barge transport proved not only technically difficult but also economically unfeasible. Analysts quickly calculated that to meet NIS’s needs, at least 145 (!) barges per month would be required. Low water levels on the Danube, a shortage of port capacities, and high transshipment costs made each voyage expensive and risky.

Another project involved building a pipeline from Hungary to Pancevo that could transport Russian oil currently reaching Hungary via the Druzhba pipeline. Although Serbia and Hungary, with Moscow’s assistance, have already signed an agreement to build the new pipeline — and China expressed interest in financing the branch — the future prospects of Druzhba itself are doubtful due to the constant expansion of European and U.S. sanctions against the Russian oil industry. Investing huge funds in such a risky project is a dubious venture.

Therefore, Serbia’s energy vulnerability persists even with the active use of risky river routes and phantom pipeline extensions.

Hybrid Oil

Commentators note that Russia’s unwillingness to lose control over NIS is not driven solely by financial motives. Behind the preservation of its share lies an obvious reluctance to allow an independent audit, which could reveal transactions carried out through intermediary companies and shadow schemes. In particular, it could expose real links with hybrid projects of Rossotrudnichestvo, networks of “Russian culture enthusiasts,” or funding of anti-Ukrainian propaganda in Serbia and neighboring countries. An open audit would mean disclosing real supply routes, actual sources of profit, and possible financial transfers between NIS and Russian security structures. Therefore, Moscow prefers to remain an “invisible co-owner” — controlling financial flows while avoiding public accountability.

Thus, Serbia has found itself in a situation of dual dependence: formally trying to avoid conflict with the West, it is in fact forced to sustain the viability of Russian schemes. And the deeper Belgrade sinks into this “gray zone” between sanctions and survival, the harder it will be for it to regain real sovereignty in the energy sphere.

Negotiations Around NIS in November: The Illusion of Neutrality

The world in which Serbia exists no longer allows one to stay “above the battle.” In the global war for resources and influence, there are no neutral sides — only those who have not yet admitted whose side they are on. Sanctions against Naftna Industrija Srbije merely exposed this fact. When on October 8, 2025, U.S. restrictions took effect, Belgrade still hoped for compromise. But a month later it became clear: energy knows no compromise. In it, as in the struggle between good and evil, one must choose a side.

NIS — a company created in alliance with Moscow and dependent on Western financial systems — became the embodiment of a duality that no longer works. The U.S. struck at Russian capital, but above all at the very idea of Serbian “neutrality.” For when your oil passes through Croatian JANAF, your payments through foreign banks, and your ownership through Gazprom, you are not independent — you are merely not yet recognized as dependent.

Washington gave Belgrade half a year to choose. A series of deferrals, special licenses, “transitional permits” — time to make a decision, not time for salvation. In February — a 90-day waiver; in March — another; in July — a special license; in October — the last extension. November 8 — the end. Now it is either an exit from the Russian orbit or a shared defeat with it.

Orban’s Activity: A Victory That Never Was

At the beginning of November, Viktor Orbán again played the role of “mediator between worlds.” After meeting with Donald Trump in Florida, he solemnly declared that he had achieved the “complete exemption of Hungary from sanctions” on Russian energy resources. Hungarian state media presented this as a geopolitical triumph: that sanctions were lifted, energy security preserved, and Orbán had proven able to maintain dialogue with both Moscow and Washington.

But Washington quickly clarified that no lifting of sanctions had occurred — it was merely a one-year postponement. It provided for the temporary non-application of sanctions restrictions on supplies through the Druzhba and TurkStream pipelines in exchange for agreements on purchasing American liquefied gas and Westinghouse fuel for Hungary’s Paks nuclear power plant.

Thus, behind the loud words about a “diplomatic victory” lay an ordinary exchange — political loyalty for one year of energy stability. Orbán received a short-term respite, and Trump gained a new market for American fuel.

This step provoked a wave of reactions in the Balkans. Encouraged by Orbán’s apparent “success,” Aleksandar Vučić began preparing his own approach to Washington, hoping to obtain a similar indulgence — this time for NIS. However, unlike the Hungarian prime minister, Vučić chose to distance himself from direct negotiations: he delegated all talks to the Russians, who, he claimed, should negotiate with the Americans themselves.

Who Will Get NIS?

Against this background, Moscow softened its stance and began speaking about the possibility of selling its share in NIS to third parties. This was the first official signal that the Kremlin was ready for a tactical retreat — at least on paper.

However, the question of who exactly will buy this share remains unanswered. Previously, experts were convinced that the buyers would be from the U.S. Now there is talk of interest in NIS from an Arab sheikh or a Greek company connected with the British oil business. It is not excluded that the Hungarian MOL company seeks to become the buyer. Russian management maintains the intrigue, demonstrating that control over NIS is not only an economic but also a political asset. And although it is officially said to be a “neutral investor,” doubts remain — will the buyer turn out to be a structure loyal to the Kremlin?

Meanwhile, Vučić carefully watches the game between the two powers. His strategy is simple — let Russia negotiate with America, and take advantage of any outcome. If the deal succeeds — he will say he “saved Serbia.” If it fails — he will remind that “it was Russia’s responsibility.” Yet no decision made will bring Belgrade freedom from geopolitical oil dependence. The illusion that one can stay “above the fray,” maintaining neutrality, ended together with the last barrel JANAF sent to Pancevo.

The introduction of sanctions against NIS became a moment of truth, clearly demonstrating that in times of global geopolitical upheaval, no country can remain on the sidelines. You are either part of the energy system of the U.S. and Europe, or a link in the Russian network. And NIS is merely another form of this choice.

CWBS Analytical Group