Relations between Serbia and Ukraine from February 24, 2022 to the present day have remained complex and ambiguous, which is usually explained by Serbia’s balancing act between its traditional ties with Russia and its aspirations for membership in the European Union.

But there are many more factors behind Belgrade’s contradictory stance.

Geopolitical twine

The Kosovo issue is a key factor determining Serbia’s policy towards both Ukraine and Russia.

Usually, when explaining Serbia’s position on Ukraine, President Aleksandar Vučić emphasizes respect for international law and the territorial integrity of all states. These arguments are presented not as imperatives, but purely as a component within the Kosovo issue. It is precisely the rejection of Kosovo’s independence and the need to preserve Serbia’s integrity, as per Vučić, that requires him personally and the Serbian authorities in general to support the territorial integrity of other UN member states, including Ukraine.

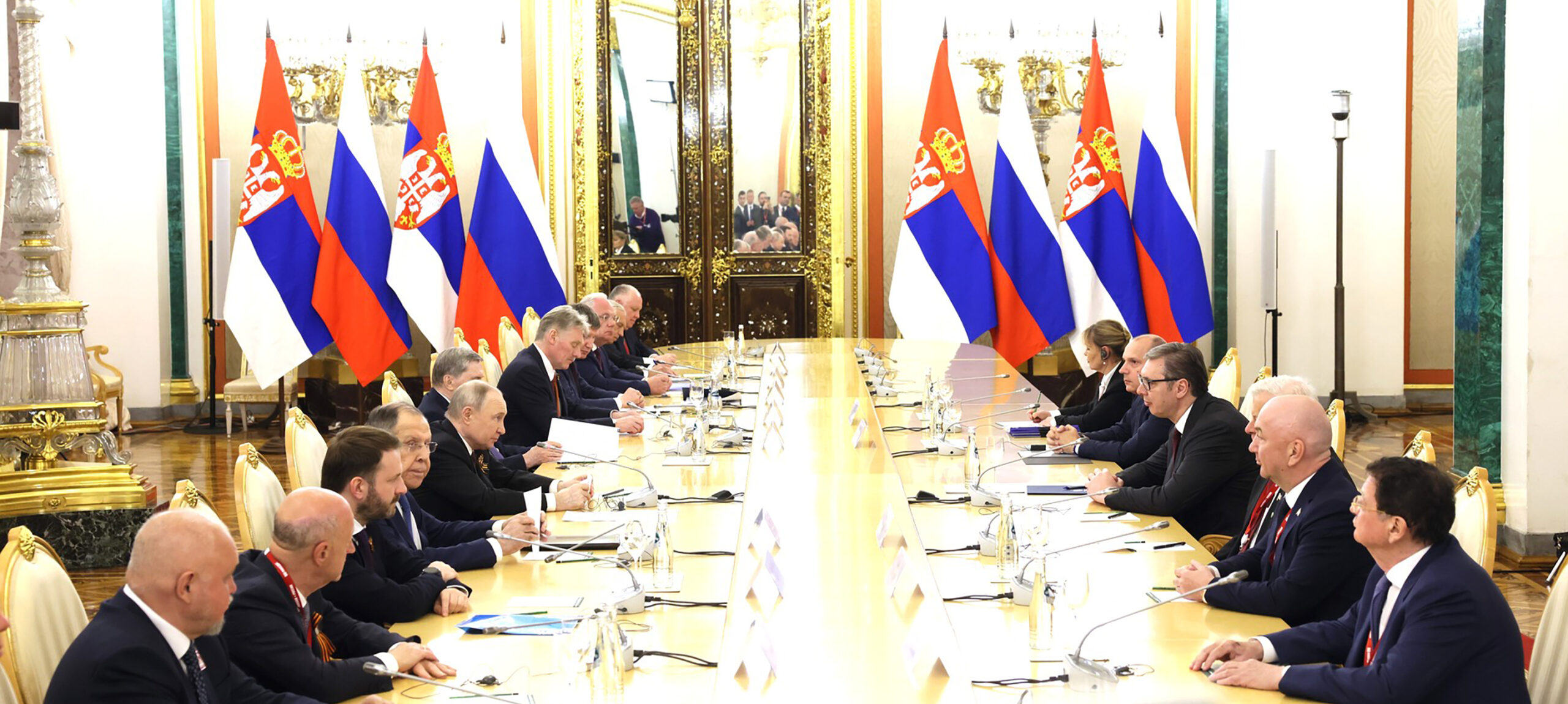

At the same time, the issue of recognizing or not recognizing Kosovo directly depends on the UN Security Council, and therefore on Russia, as one of the members of that body. This forces Belgrade to maintain special, friendly relations with Moscow.

This geopolitical twine leads to a paradoxical foreign policy line: while Serbia declares its support for the territorial integrity of Ukraine, it refuses to introduce any restrictive measures (sanctions) against Russia, which occupied part of Ukrainian territory and demands that the international community recognize its right to annex several Ukrainian regions.

Geopolitical maneuver

The best illustration of Belgrade’s position was the participation of the Serbian president in the “Ukraine – South-East Europe” summit in Odesa (Ukraine).

Although the visit could have been seen as an anti-Russia step and a gesture of support for Ukraine, that is, a country at war with Russia, Vučić managed to present his participation in the event from a different perspective.

First, he emphasized humanitarian support for Ukraine, noting that Belgrade was ready to help Kyiv purely in the humanitarian field – by providing assistance for schools and participating in the reconstruction of “one or two cities or regions”.

The Serbian leader, of course, said nothing of military support. To emphasize his neutrality, Vučić did not even take part in the commemoration of the fallen defenders – he did not visit the Alley of Heroes in Odesa unlike other summit participants to lay flowers at the site.

Secondly, the Serbian president clearly and unambiguously linked his participation and position at the summit with Ukraine’s stance on Kosovo. He expressed gratitude to Ukraine for not recognizing Kosovo’s independence and for refusing to invite representatives of Pristina to Odesa, stressing this thesis repeatedly.

Serbian pro-government media presented the absence of the Kosovo delegation at the summit as a “diplomatic victory for Serbia,” focusing on this aspect of the president’s visit.

Thirdly, while in Odesa, the Serbian president was able to send a “friendly signal” to Moscow by stopping short of supporting the summit’s final declaration, which condemned Russian aggression and called for more sanctions against the Russian Federation.

Commenting on his decision, Vučić emphasized that he “did not betray Russia.”

Judging by the reaction from both Kyiv and Moscow, he once again succeeded in pulling off yet another complex geopolitical maneuver.

Gas friendship

Another factor that cannot be ignored when analyzing Belgrade’s approach to building relations with Moscow and Kyiv is economy. More precisely, Serbia’s attempts to convert their multi-vector geopolitical position into profitable contracts.

So, on the one hand, Serbia – as a country that does not align with Russia sanctions – seeks to purchase gas from Russia’s Gazprom at an exclusive, preferential price.

It is clear that cheaper energy, compared to other European countries, reduce production costs for industrial enterprises in Serbia, create conditions for profitable operation of energy-intensive industries, make it more beneficial for investors to inject money in Serbian industry, allow keeping prices for utility services for the population relatively low, and generally contribute to increasing budget revenues and economic development. At the same time, most of the listed points have an impact not only on the economy, but also on politics, because they secure electoral support for Vučić and money for projects that contribute to growing public ratings for himself and his government.

In conditions where Serbia is not subjected to any sanctions from the EU for refusing to introduce restrictive measures against Russia and rejecting the idea of diversifying energy supplies, and where Belgrade sees no y contradictions between statements about supporting the territorial integrity of Ukraine and the desire to remain friends with the aggressor state, the Serbian-Russian “gas friendship” may remain in place.

The only question is whether the cost of “cheap gas” for Serbia will increase. And this isn’t about the money.

National interests

As previously noted, Moscow is now demanding from Belgrade stricter control over Serbian arms exports in order to put to a halt any possible “schemes” of Serbian defense products getting into Ukraine’s hands. Russian intelligence recently accused the Serbs of trying to “shoot the fraternal Russian people in the back”. The statement came amid allegations of Serbian arms supplies to Kyiv.

It should be noted that the defense (dual-use) industry is another area of Belgrade’s pragmatic economic activity. Vučić has repeatedly reaffirmed the right of Serbian enterprises to produce and sell weapons, military equipment, and ammunition on the world market, emphasizing that this is about ensuring the operation of factories and plants and preserving jobs. Belgrade portrays Serbia’s alleged supplies of weapons/ammunition to Ukraine (allegedly carried out through third countries) not in the context of supporting Kyiv, but as a concern for its own industry and a desire to address social issues.

Recently, the Berlin-based newspaper Tagespiegel wrote: “The government in Belgrade constantly emphasizes that it looks only at its own interests. Sanctions against Russia, it claims, do not correspond to national interests. However, profitable arms sales do.”

Serbia, apparently, will refute the latest accusations coming from Russian special services, defending its right to participate in the world arms market. But Kyiv should not rejoice as this is about Belgrade’s desire to continue making money, not about the will to help Ukraine in its fight against the aggressor.

The game continues

As we can see, Serbia’s policy towards Ukraine is determined by two key factors:

1. Kosovo.

2. Serbia’s own economic interests.

The previous determines support for the territorial integrity of Ukraine, albeit limited and somewhat declarative.

The latter is used to explain the lack of sanctions against Russia, but, at the same time, to justify the need for arms exports, even in the wake of allegations that weapons or ammunition are making their way to Ukraine.

It will be increasingly difficult for Belgrade to pursue its policy of limited support for Ukraine, based on these factors. The reason is Russia’s position.

As noted above, Moscow wants to close all the gaps through which Serbian weapons or ammunition allegedly reach the Ukrainian army. In a situation where the future of the gas contract depends on the resolution of this issue, Belgrade may turn toward Moscow.

The Kosovo factor is even more complicated.

Putin’s attempt to speculate and manipulate the Kosovo issue to justify the annexation of Ukrainian territories could turn all of Vučić’s traditional arguments about the need to protect the territorial integrity of states “head over heels” and turn the Kosovo issue into a toxic one for Ukraine. It is obvious that the Serbian leader will need extraordinary skill and creativity to pursue his intricate game, posing as a friend to both Moscow and Kyiv.