The Montenegrin National Statistics Office, Monstat, released the results of the 2023 census a year and a half after it was conducted. While some data had been published earlier, the questions related to national, ethnic identity, religion, and language were notably delayed. These results revealed a significant drop in those identifying as Montenegrins, alongside a rise in those identifying as Serbs. Many attribute this trend to the fact that, since 2020, Montenegro has been governed by parliamentary majorities partially backed by the Serbian Orthodox Church and the Serbian state.

In my previous op-ed for CWBS, I discussed the role of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Montenegrin politics. The census results offer further evidence of how the Church has come to dominate the political and social processes in the country. Montenegrin identity is under siege from Serbian nationalism, which views Montenegrins as a sub-ethnicity within the larger Serbian ethnos. This ideology, embraced by the current regime in Belgrade and the Serbian Orthodox Church, seeks to undermine Montenegrin identity under the guise of protecting Serbian identity.

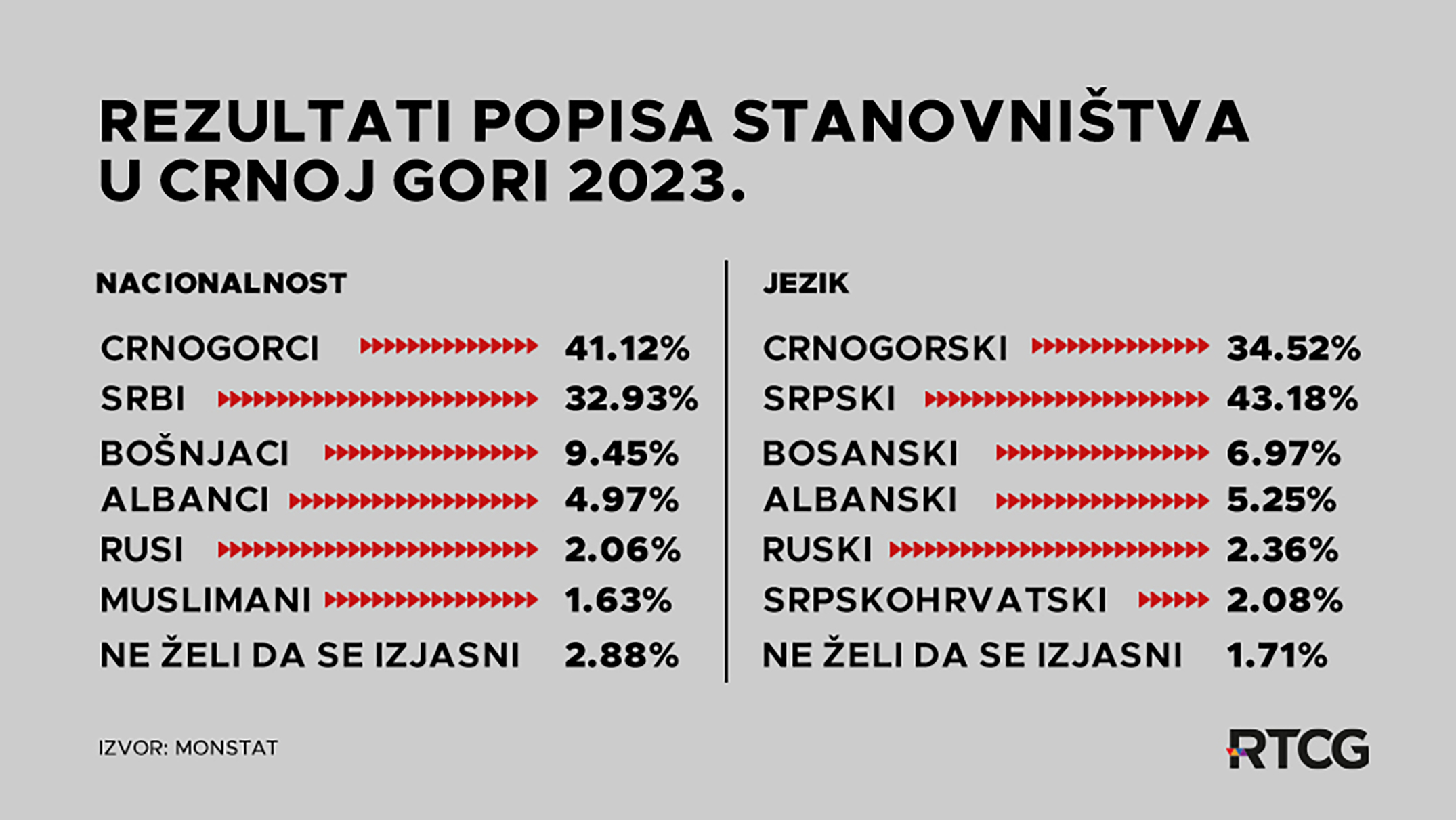

Montenegrin identity has long been fluid, a topic of much scholarly debate. The process of its formation and consolidation is well-documented in both popular and academic literature. What is often overlooked, however, is the role of the Serbian state and the Serbian Church in shaping it. In the 1948 census, Montenegrins made up 90% of the population of Montenegro. By 1981, this number had dropped to around 70%, while Serbs accounted for only 3%. The Serbian nationalist revival in the late 1980s further diminished Montenegrin identity, with the number of Montenegrins falling to 60% and Serbs rising to 10%. A decade under Slobodan Milošević saw Montenegrin identity plummet to 42%, while the number of Serbs increased to 32%.

After Montenegro regained its independence in 2006, the 2011 census showed a reversal of this trend. Montenegrins rose to 45%, while Serbs dropped to 29%. However, following the political shifts of 2020, the most recent census shows Serbs increasing by 4% to 33%, and Montenegrins decreasing by 4% to 41%.

This trend is not confined to Montenegro alone. Across the region, the number of people identifying as Montenegrins is in decline. In Serbia for example, the Montenegrin population has fallen from 140,000 in 1991 to fewer than 20,000 in 2021. Given that there are only around 300,000 Montenegrins globally, it is not overstated to say that our small nation is facing the threat of extinction.

The main driver of this trend is the ethnocidal campaign waged by Serbian nationalism. The Serbian Church in Montenegro promotes Serbian identity, language, and national mythology. Montenegrins are often dismissed by Serbian clergy as “bastards of communist ideology.”

These changes are not driven by migration; rather, they reflect a shift in how the same people identify themselves from census to census. The Serbian Church and the Serbian state have played a key role in shaping the latest census results, which Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić recently celebrated in a speech to Serbia’s security and intelligence agency (BIA).

The largest faction of Montenegro’s ruling coalition after the 2020 elections, the “For the Future of Montenegro” coalition, headquartered its campaign in the “Serbian House” in Podgorica. This building, which dominates the city’s modest skyline, was fully financed by the Serbian government and prominently commemorates President Vučić on its entrance. Serbian government minister Selaković, attended and opened in 2019. This is just one of the illustrations of Serbia’s active investment in Serbian organizations in Montenegro.

Paradoxically, most Serbian politicians and leaders in Montenegro are not from Serbia. They are ethnic Montenegrins who claim Montenegro as a Serbian state, not a separate entity.

Serbian nationalism has gained momentum in the Montenegrin media as well. Three of the four largest TV stations with national frequencies are owned by Serbian companies, two of which are controlled by individuals close to Vučić. During his recent visit to Montenegro, Vučić felt quite at home, insulting Montenegrin government officials, journalists, and civil society while being interviewed by these very outlets.

Since 2020, much energy has been spent preventing pro-Russian Serbian nationalist elements from gaining control of Montenegro’s security and defense sectors. However, the Serbian Church and nationalist movements have turned their attention to Montenegro’s cultural and educational institutions. A prominent pro-Russian Serbian nationalist was appointed rector of the country’s only state university, while another far-right activist became Minister of Education. Through the highly centralized education system, this minister has replaced numerous school principals with nationalist loyalists. One of the outcomes of this shift has been a disturbing trend of high school prom celebrations where 18-year-olds brandish Serbian nationalist insignia and sing nationalist songs.

Serbian nationalist organizations and cultural events have proliferated across Montenegro since 2020, giving rise to a new cultural landscape dominated by Serbian influence. Montenegrin actors and singers who subscribe to this nationalist agenda have found platforms to succeed, not only in Serbia but also in Moscow. Serbian companies have also gained ground in Montenegro, most notably MTEL, a telecom company that has become a major provider of mobile, internet, and cable services. MTEL wields its marketing budget to exert political influence, while other cultural icons like tennis star Novak Djokovic are used to sway Montenegrin public opinion in favor of Serbia.

The Serbian Church and state goals in Montenegro are far from accomplished. They have several objectives on their agenda to further consolidate their influence in Montenegro. The Speaker of the Montenegrin Parliament is pushing for the construction of a Serbian chapel on Lovćen, a mountain with deep significance in Montenegrin national mythology. In addition, there is a strong push for liberalizing citizenship laws to allow Serbian citizens to acquire Montenegrin passports. This move could dramatically alter Montenegro’s political landscape, potentially leading to constitutional changes that would align the country more closely with Serbia.

These efforts, combined with Serbia’s subversion of Montenegro’s path toward EU integration, have created a perfect storm that threatens Montenegro’s long-term independence. If these trends continue, Montenegrins risk becoming a minority in their own country, with their identity absorbed into the Serbian nationalist agenda and exploited for the interests of the regime in Belgrade. This would not be the first time—let us simply recall the shameful role Montenegro played in the wars of the 1990s.

The articles published in the “Opinions” column reflect the personal opinion of the author and may not coincide with the position of the Center

Ljubomir Filipović. Montenegrin political scientist