Census as a political spectacle

In Montenegro, the socio-political situation is set to further aggravate. And the reason for that is not only the almost three-month absence of the new Government while the technical cabinet continues its work. This time, the political crisis was caused by a purely technical, statistical event – the census of the population and housing stock, which was scheduled for November 1-15 before being postponed for a month.

The population census in most European countries is, first of all, a useful and important tool to have an outlook for the future in all areas of the country’s life and understand he issues of today. But in Montenegro, the population census has turned into a political spectacle that threatens to divide along ethnic lines the country, which until recently was considered a role model of tolerance in inter-ethnic and inter-religious relations.

As a reminder, according to national legislation, censuses shall be conducted every 10 years. The latest was held back in 2011. According to that census, 44% of the population consisted of Montenegrins, 28% – Serbs, 6% – Bosniaks, 5% – Albanians and the rest – Roma, Muslims, Yugoslavs, and Egyptians. The next census was supposed to take place in 2020 but it was disrupted by the Covid pandemic. Immediately after it was called off, the new, pro-Serbian government began preparations for the census, which at the beginning of 2023 turned from a statistical event into a political project. The main role in this transformation was and is played by the pro-Serbian and pro-Russian parties and movements of Montenegro, rallied around the coalition For the Future of Montenegro, the successor of the Democratic Front.

The questionnaire has almost 80 questions, but three of them – on ethnic and religious affiliation, as well as the language – have been at the center of political confrontation. That is, a purely political problem was put in the epicenter of a routine statistical event – whether the Montenegrin identity will be preserved or it will be gradually destroyed, and over time this will lead to the change of the country’s constitutional system. To achieve this goal, a so-called “Serbization” of the country began. This term is used by political scholars and regional media to identify attempts to artificially increase the number of the Serbian population and spread narratives of the “Serbian world” in Montenegro.

A bit of statistics

In 2017, the International Organization for Standardization separated the Montenegrin language from the Serbian one and gave it the corresponding geocode – ISO 3166-2:ME. But even today, the Montenegrin language has not become a truly state language. Indeed, Montenegrin is very similar to Serbian and Croatian, however, only Serbs allow themselves derogatory remarks mocking this language.

According to data posted by the Center for Democracy and Human Rights (CEDEM), 48.6% of respondents in Montenegro say they speak Serbian (+6% compared to the 2011 survey data), while 36% (the number has not changed) speak Montenegrin, and 2.6% (-4%) – Bosnian.

The confessional preferences of Montenegrin citizens show a high level of trust (80-89%) in the Serbian Orthodox Church (a few years ago it changed its name somewhat to become the Montenegrin-Littoral Diocese of the Serbian Orthodox Church). This is quite understandable – there is practically no other Orthodox Church in the country, since the Montenegrin Orthodox Church has not yet been recognized as canonical and has little support (about 10%). The SOC, with the support of the Serbian authorities, became not only an influential spiritual force, but also a powerful political tool in the Western Balkans.

The situation of the ethnic self-identification of the country’s citizens is somewhat better. The Center’s data show that the majority refer to themselves as Montenegrins: 46.2% (+2% compared to 2011 data), while 32.8% (+4%) refer to themselves as Serbs, 7.7% (+1%) – as Bosniaks, and 5.1% (unchanged) – as Albanians and others.

Is the actual purpose of the census the “Serbization” of Montenegro?

The majority of Montenegrin Serbs live in the north and several littoral areas. This creates, hypothetically, favorable conditions for the formation of two entities (Montenegrin and Serbian, following the example of BiH) or a Community of Serbian Municipalities (just as it is planned in Kosovo), which will threaten the independence and integrity of Montenegro.

Political forces that are interested in such a scenario have launched the “Serbization” of society with the aim of assimilating Montenegrins in their own country. The former leader of the pro-Serbian and pro-Russian Democratic Front, M. Lekic, spoke quite frankly about this: he called to show that “we, the Serbs, are more than others”, and also to refer to themselves during the census as Serbs, supporters of the Serbian Orthodox Church, who speak Serbian. No more, no less. This is clearly pressure on future census participants and an attempt to violate freedom of expression.

The SOC also joined attempts to “Serbize” Montenegrins. For example, recently the Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church, Porfirije, accompanied by the leaders of some right-wing nationalist Serbian parties, visited Montenegro. In one of his sermons, he called on believers to refer to themselves as Serbs. Which, as expected, caused a wave of sharp criticism on the part of the Montenegrin patriotic forces.

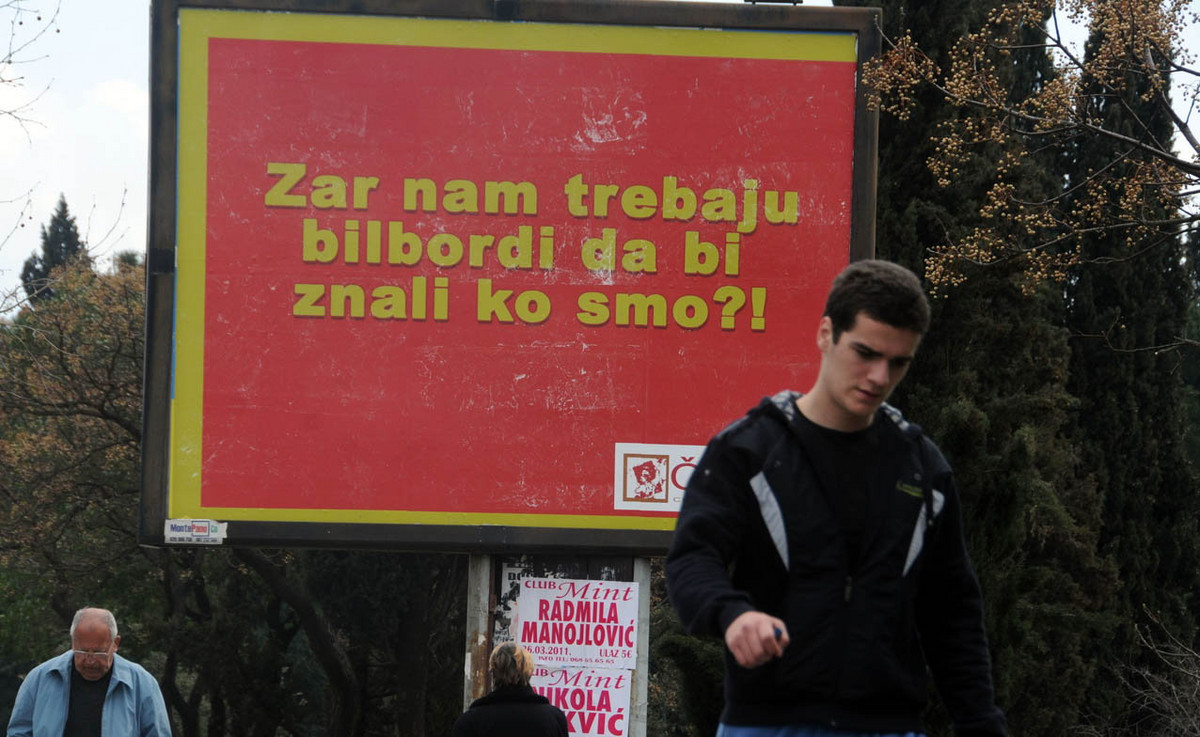

The diplomatic row between Montenegro and Croatia unfolded over billboards spotted in the southern part of the country and in areas near the Croatian border. Croatian researchers of the 18th and 19th centuries, B. Bogisic and R. Boskovic, are depicted on them, accompanied by a provocative inscription – “Proud to be a Serb.” Of course, this caused discontent in Zagreb.

Today, Montenegrin cities look like they are on the eve of another election – they are filled with billboards calling on citizens to refer to themselves as Serbs during the census.

The opposition calls such actions of Montenegro’s opponents as “ethnic engineering”, that is, a large-scale and artificial altering of the country’s ethnic composition. It’s hard to disagree with that.

Problems with the Montenegrin census

It is clear that in such a tense socio-political and media situation there is every reason to doubt the objective results of the census. Indeed, it is not held at Russian gunpoint, like it was in the temporarily occupied Crimea and Donbas. But the ideological and media pressure on ethnic Montenegrins is quite powerful, accompanied by a deepening division of society along political, religious, and ethnic lines.

There are also questions about the mechanism of the census as such. In particular: how and who will conduct surveys abroad; how well prepared are the 4,500 personnel who will run the survey in Montenegro, most of whom are students and unemployed cititzens; is the new Government able to ensure the security of the census process and logistics; why is there no translation of poll questions into Albanian, on which the Albanian minority insists; and many other issues. Some sociologists raise questions about the methodology of preparing, conducting, and processing the results of the census.

A week before the scheduled start of the census, proposals were drafted regarding the composition of the new Government, which should be considered by the Assembly this week. In the case of a positive vote, the transfer of power will begin in executive bodies of all levels. It is natural that the process could have a negative impact on the actual census and processing of its results, complicating technical and organizational issues.

The aggravation of the socio-political situation ahead of the census, as well as the mentioned technical problems, gave the opposition parties and the national councils of Albanians, Bosniaks, Roma, and Croats reasons to submit a proposal to postpone the census for three to six months – until the problems are resolved and the situation in the country is normalized. On October 18, the European Parliament also spoke in favor of postponing the census for some time until the situation stabilizes, which will allow for conducting it in accordance with the EU requirements and international standards.

Four opposition parties called on their supporters and Montenegrin citizens to boycott the November census and offered the government to postpone it until next spring. According to the estimates of some experts, up to 10-15% of the population may join the boycott. And then the results of the census cannot be recognized as objective and reflecting the real picture of the Montenegrin population. Then almost EUR 5 million will go to a waste.

Thus, running a census of Montenegro in November 2023 would be impractical for the following reasons:

- unstable political situation and the threat of political, ethnic and, confessional division of Montenegrin society;

- the media and ideological campaign launched some political forces, which, with support from abroad, are trying to alter the Montenegrin identity, which will threaten the existing constitutional system;

- a number of technical and methodological issues of executing the census,

- in case of a “successful” attempt of the first ethnic engineering operation in the region to alter the national identity of the population, it will become “popular” elsewhere and lead to other forces being willing to repeat it.

Postponing the census for a month probably will not significantly affect the process, since this period is too limited to fully normalize the socio-political situation in Montenegro.